Introducing change to your organization can feel like an uphill battle, but it doesn’t have to. Here are some tactics to implement for more successful transitions.

One of my favorite business jargon phrases is “change management.” This encompasses the approaches used to prepare, support, and help both individuals and teams make organizational change happen. Boiled down, we’re really talking about human behavior change.

As a leader, I have heard people discuss this topic a lot. When looking towards the future, colleagues will generalize that "we need better change management.” When looking back retrospectively, they’re more prone to, “That change wasn’t managed effectively.” If you’re really looking to get some nods from around the table it’s one of those things you can say with very little pushback, because it’s almost always true.

However, what I rarely hear or see are tactical change management plans from engineering leaders who are proposing an idea or a project. I see technical plans. I see project plans. But I nearly never see plans that nourish change in a project that could be instrumental in certifying its success.

Change is inevitable. The need for individuals and teams to modify thinking and behaviors in response to change is critical. As leaders, it’s our whole job to enable organizational change. To get great at doing that job, we must practice change management strategy as part of our leadership craft.

Strategies to try depending on context

The most effective change management strategy for your project will vary depending on the type of shift you’re trying to implement and the environment the change will occur in. Here are three tactical strategies that you can experiment with as part of your leadership toolkit to find the one that best suits your situation.

1. Cheerleading

The strategy that I implement most, as it comes most naturally to me, is what I refer to as “cheerleading.” In a sports context, cheerleaders exist to engage an audience. Using high-energy, rhyming chants that people can’t help but shout along to, they pull the crowd in and transform them from observers to active participants. Cheerleaders use the superpower of their own enthusiasm to engage and celebrate. They facilitate a temporary bubble of community that exists during the course of a game.

In change management, cheerleading is about enthusiastically and playfully inviting others into a change and loudly celebrating early signs of that change. It’s about creating a highly visible opportunity to be a part of a temporary, collaborative, joyful community.

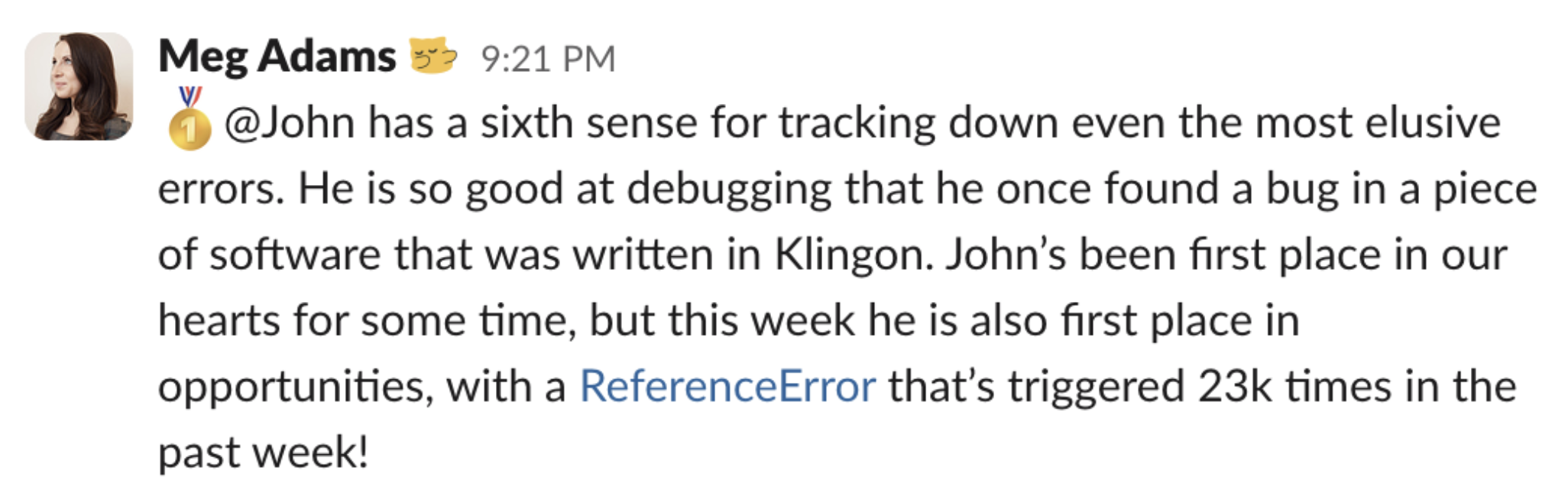

I always find cheerleading useful, but I find it works best for cultural changes and changes that can be adopted slowly. The most recent example of a cheerleading strategy I applied was in the context of helping an organization activate toward a “zero exceptions” culture. The change needed was for teams to review, self-assign, and resolve errors triggered within the systems that they owned.

We created a “greatest opportunity for greatness” leaderboard where we posted the owners of the top five errors being triggered in our environments each week, celebrating with public accolades once those errors were resolved. Our leaderboards were public and intentionally light-hearted, with ever-changing themes. Here’s an example of someone’s leaderboard entry from a week where the inspiration was the hyperbolic introductions from Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Competition:

The important thing with cheerleading is consistency. The most common mistake I see is starting incredibly strong and then getting too busy to maintain the ritual you’ve put in place.

With the cheerleading strategy, you are creating a public and shared narrative for a temporary community. You are its caretaker. It only exists because of your attention and enthusiasm and, without those things, it dies. Be sure your initiative has a multi-person support infrastructure and be sure to begin and end it with intention. Abandoning an effort like this midway is confusing and implies that it’s not actually all that important.

2. Bright Spots

Switch: How To Change Things When Change Is Hard by Chip and Dan Heath is on the short list of must-read books I give to new managers. It’s a quick education on human behavior and change management theory. The concept of “bright spots” is taken from this work.

Bright spot theory encourages people to focus less on what isn't working or needs to be fixed, and more on what is working and how it can be cloned. Look for a place where the thing you want to create already exists; find out why it’s working; and expand that working model elsewhere in the organization.

I notice this strategy to be particularly useful to reach for when you feel you’ve tried to drive something forward and it just isn’t working. When I feel frustrated with a change, I take that as a signal that I should stop, look to my bright spots, and see what there is to learn.

This strategy was effective when I applied it to help an organization improve the discoverability of their data. We needed to change the mindset of employees from a mistrust and reluctance toward even trying to look for it, to consistently accessing and using high-quality data.

In this scenario, the bright spots were the few teams who were effectively using data to make decisions. We sought out what was working in those environments and found something surprising: each of the disparate teams had a personal connection to exactly one data architect (let’s call her Anna) who worked on a different team. Anna was naturally helpful and had deep knowledge of the organization’s core data sets, having designed many of them herself. These teams were leveraging their friendship with Anna to ask for help when they couldn’t find their way rather than getting themselves lost in the data maze.

“Who is friends with Anna?” and “How do we systematize the knowledge Anna has?” weren’t two questions that would have been at the top of the company’s list to ask in pursuit of improved data discoverability. But, they were critical questions that ultimately guided the team to build robust and personalizable wayfinding functionality into the data catalog, bringing subject matter expert guidance directly into users’ workflows. The active user count for the data catalog began to increase quarter over quarter.

The most common missed opportunity I see with this strategy is not enrolling the people associated with bright spots into your vision. Learn what’s going well in their approach; acknowledge them for what they’ve helped to create; and then invite them to be evangelists and champions of the change you’re implementing. Ask them to look for opportunities to talk about what they know with others. It’s an easy way to force multiply your change efforts.

3. The Gannet

A gannet is a seabird that can both fly high in the sky and dive deep into the ocean. This strategy, like its namesake, is about approaching a change that needs to occur from two separate dimensions: the top and the bottom. This looks like designing a broad communication and guidance plan for the masses and also designing a more specific communication and guidance plan for individual outreach.

This strategy is best for changes that are absolutely required and must be implemented on a prescribed timeline. I consistently use this strategy when many teams must complete a migration task on the systems that they own.

For example, I previously applied this strategy when supporting an organization’s move from one data warehouse to another; this included the migration of hundreds of data scripts, a large percentage of which didn’t have any clear owners. Here, our aim was to encourage individuals to take ownership of translating scripts and validating resulting dataset changes. The core change needed was inaction to action.

To create broad awareness of the importance of the initiative, we designed guiding communications with self-service migration runbooks that went to the full technology group. Unfortunately, the number of people who took action from that sort of broad communication was, and often is, incredibly low.

To counterbalance, we additionally organized individualized outreach for each team, sending more personal notes pointing people to those broad comms, ensuring that they’d read and understood them, and offering extra support and space for questions if needed. The broad comms set the container, letting people know that the initiative was important for the whole organization, while the personal notes encouraged the needed action to occur.

A mistake that can be made here is duplicating (copying and pasting) the exact message used in high-level comms for low-level – and vice versa. This results in many sources of truth that can quickly become outdated as time goes on.

To help here, create a centralized version of the “how to” material you’ll broadcast, in this case, a migration runbook. When you’re then reaching out to members of the company on both a macro and micro scale, link to this consolidated source. This will help streamline communication and will simplify the process of updating, altering, and correcting the original content as things change over the course of your project.

Start now!

If you’ve not been actively strategizing and practicing change management, the odds are you aren’t very good at it yet. You probably won’t be for some time. So start now! Try some of these strategies on and see if they work for you. Make some mistakes and then learn from them. Most importantly, have some fun while you do it. Humans are wonderful and weird, so playing in the space of human behavior change can be wonderful and weird, too.

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.jpeg)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

(1).png)

(1).png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)