Learn about the actionable steps you can take to achieve an outstanding quality culture via experimentation.

When joining teams and companies as a dedicated testing and quality specialist, I’ve repeatedly observed lots of problems. The delivery of changes has been slow. The product has not met expectations. People have found lots of regressions. Reputation was poor, confidence was lacking, and team morale was low.

In these instances, the need to grow a quality culture was clear to everyone, but it wasn’t all too apparent what steps needed to be taken to achieve such a culture.

Getting started with experimentation

Experimentation can serve as a good guiding tool in any manner of situation, including personal growth, team transformations, and organizational change. Below are some key elements to help you get started.

Create transparency. Start by observing and gaining clarity on the status quo. Find out pain points, needs, concerns, and wishes. Shine a light on the current system at work. Observing what people say and do can provide us with indicators of day-to-day happenings. Come from a place of curiosity and try to keep judgment at bay; people have good reasons to behave as they do.

Gather options. If there is a diverse pool of opinions on how to tackle a certain matter, collect as many different paths of action that you can try out. Make sure to hear everyone involved in the experiment. People have had different experiences and will therefore provide diverse options. Get everything on the table so you can make an informed decision together.

Keep an open mind. Whatever way you choose to tackle the challenge, remember that this is just a first try and not carved in stone. Ultimately, the purpose of experimentation is to get you toward a specific goal. And even failure can help inform you of how to get there.

A step-by-step guide

Taking all the above points into consideration, the steps below will help you navigate experimentation:

- Review the currently known challenges specific to your organization or team. Update where needed.

- Of the listed challenges, pick one to tackle next. Those who are involved in the experiment can make this selection based on their current, biggest concern or if a particular challenge is a quick win to be solved.

- Think about potential solutions and list them. You might be aware of several options already. Feel free to come up with new ideas according to recently gained knowledge.

- Of the listed options, pick one to try out. It's only the first choice, which does not have to be the final one.

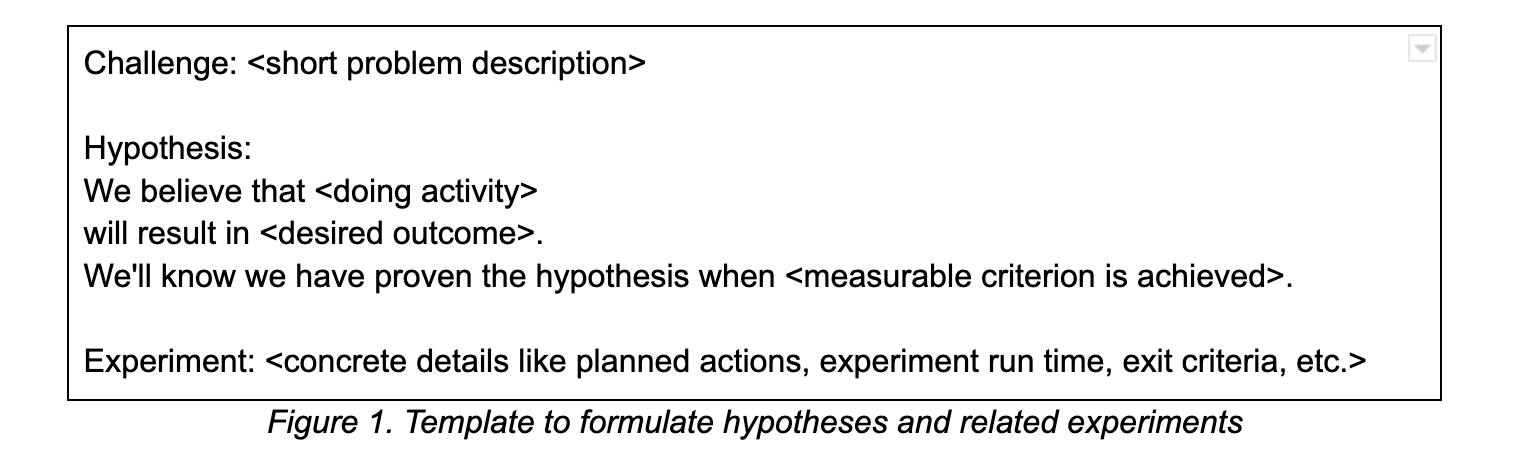

- Once you have decided what path you’d like to try first, craft a measurable hypothesis. You need to be able to test it to show if the problem has been solved or if another option should be put to the test.

- Design a concrete experiment to test the hypothesis. It doesn’t have to be scientific, a lightweight probe is sufficient as long as it serves to validate the hypothesis.

- Run the experiment. Keep track of the hypothesis measurements.

- Evaluate the experiment. If it has proven the hypothesis, adopt the new practice; if not, repeat the process and use the insights gained to inform the next experiment.

Download the template

Make experiments safe to fail

The above guideline seems pretty straightforward, but a smooth journey from beginning to end is rarely promised. Success sometimes comes after failure, so whatever you try, be aware that change takes time and patience.

Setbacks may arise for simple reasons such as it not being the right time for your team or organization. People might not be ready, foundations might not be in place, and too many other topics may be going on for further change to be introduced. Change fatigue is real, so let’s be mindful not to run too fast with our experiments for people to follow.

Experiments should be low-cost to try, and safe to fail. If there is a perceived pressure for something to work out, it’s not an experiment anymore. The outcome of experiments should always lay firmly in the “unknown” category. If it doesn’t work, that’s fine! Importantly, there wasn’t too much invested and insights were gleaned that can be used to push future experiments toward success.

What to do when you “fail”

If you think an experiment was a success, yet behavior didn’t change, then there’s probably more to it. Maybe there’s a hidden element that hinders people from adopting a new practice. Maybe it’s a lack of knowledge or confidence, missing incentives, or higher rewards for different behavior. Maybe it’s just someone trying to impose something that does not fit the current context of the team! Find out what it is and go deeper into the root cause to solve the underlying issues and affect real change.

Maybe it’s none of the above. Maybe there wasn’t enough incentive for people to put their “all” into this experiment. I’ve seen this a lot, with everyday tasks quickly becoming the main priority over a new experiment. Adequate motivation can steer the ship in the right direction but, often, the systemic issue at play cannot be so easily resolved. Business requirements will usually trump work on any other experimental initiatives.

To remedy these sorts of scenarios, it can help to be very explicit about why a certain experiment is taking place, as well as keeping them timely and instantly valuable for people. Making sure experiments are front of mind for everyone involved is useful here. For example, tracking the progress in a place where everyone can see it all the time, setting up automated reminders, or using a visualization like the continuous improvement canvas by Willem Larsen.

At best, make the experiments as small as possible so that as much learning can be generated in a shorter time frame. I still often need to remind myself to take “many more much smaller steps” as GeePaw Hill puts it, and to run “many small, simple, fast, frugal trials” as Linda Rising advocates.

Keep your biases in check

Stay aware of your biases. There have been a few times when I’ve invested a lot in a long-running experiment. In these cases, sunk cost fallacy made it hard for me to acknowledge and accept that I should have stopped it earlier (or just designed it a lot smaller in the first place). Other times, I wanted to prove the hypothesis so much that I looked for any evidence to support this scenario instead of the general data available to me – confirmation bias was actively at work.

In either case, you should always stick to the facts and the observed behavior when evaluating an experiment.

Experiments allow learning on all levels

Personally, I have had a lot of positive experiences using experiments to overcome challenges. Not everything I aimed for worked out, yet I always walked away having learned more about a specific situation.

Micro impact

For example, at my current company, I wanted to establish whole team ownership for holistic testing and quality. To get us closer to this goal, I promoted pair testing. But I quickly realized that talking about pairing wasn’t enough to convince my teammates. Instead, they needed to feel the benefits for themselves.

Therefore, I ran an experiment to get my team into pairing situations. One of the ways this manifested was by requesting a colleague to stay right after our daily meeting to ask questions about a change they made. I would show my screen, we would get into a conversation, I would interact with our system, and we would start pairing – without talking about it once.

In doing this, my team realized how valuable fast feedback without waiting times or context switches can be. As the experiment evolved, step by step, the team developed skills to share the workload, learn faster, become more resilient, and deliver better product outcomes together. Gaining experience through experimentation led to a change of beliefs and an actual behavioral shift.

Macro impact

In one of my previous companies, experimentation managed to help on an organizational level, allowing tech leadership to get closer to a clear mission.

Here, we wanted to improve the testing and quality culture of the product teams by leveling up their knowledge, skills, and practices. As the main lead of this tech initiative, I designed an experiment that included custom-tailored trials with a set of pilot teams to help them adopt new practices. How? Through experimentation. Together, we identified their problem areas, gathered ideas on how they could improve, and came up with targeted experiments. For example, one group tried cross-team ensemble testing sessions to discover surprises before major releases. With our support, half of the teams figured out solutions to their specific challenges. The other half continued trying new approaches to discover what works for them.

Overall, the pilot teams were able to improve in one way or another. People felt safer and became eager to try out new ways, cultivating a stronger learning culture.

Culture is the foundation for quality

If you want better quality outcomes, a more valuable solution, and happier teams, foster a learning culture based on experimentation to help you move forward. Whatever your challenge is, start small and start now. Stay curious, keep experimenting, and continue learning together.

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.jpeg)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

(1).png)

(1).png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.jpg)

(1).png)

.png)

(1).png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)